Lawn Maintenance

Authors: Doug Soldat, Paul L. Koch, and John C. Stier

Rev: 12/2022

Item number: A3435

Introduction

Maintaining a beautiful lawn can be an enjoyable recreation and add significant value to your home. The amount of time spent will determine the quality, with results ranging from high-maintenance lawns that are lush, watered throughout the summer, and virtually weed free to medium-maintenance lawns that have some weeds and may be allowed to go dormant during the summer to low-maintenance lawns that receive little to no fertilizer and are mowed infrequently. This article describes the basics of lawn maintenance for each level of input.

Mowing

Mowing is the most important factor in keeping a lawn healthy. There are a few considerations for good mowing technique:

Cutting height and the 1⁄3 rule

Keep the lawn mowed between 2½–3½ inches tall. Use the lower mowing heights for higher quality lawns and the higher heights for lower input lawns. Follow the “1⁄3 rule” for mowing: never remove more than one-third of the leaf tissue at any one mowing. For example, if the turf is 4 inches tall, set the mower to cut it no lower than 2½ inches tall. Removing more than one-third of the leaf tissue at one time makes the turf more susceptible to environmental stresses and pest damage, slows regrowth, and exposes the soil to light, which promotes germination of weeds.

Mowing frequency

A plant’s rate of growth is constantly changing depending on temperature, time of year, water, and soil fertility. As a result, it’s better to mow when needed rather than on a fixed schedule. Lawns may need to be mowed two times a week during spring, or every two weeks during a hot, dry summer.

Keep mower blades sharp

Properly balanced and uniformly sharpened blades give a clean cut. Dull mower blades tear the grass rather than cut it. The frayed tips of torn leaves dry out quickly, giving the lawn a brownish to whitish appearance. The turf loses more water from the frayed leaf tips and becomes more susceptible to diseases and environmental stresses. Depending on the amount and roughness of use, mower blades need to be sharpened every 1–3 years. Many hardware stores and turf equipment dealers offer this service for a nominal charge.

Mow when the turf is dry

Cutting wet turf causes the clippings to form clumps on the lawn and can be dangerous for the operator, especially on wet slopes.

Mulch lawn clippings in place

Do not collect grass clippings unless they are needed for composting or mulching, or are so thick on the ground that they may smother the turf. Leaving the clippings in place has several advantages. First, the clippings contain nitrogen and other important nutrients; leaving them in place returns the equivalent of about 1 pound of nitrogen per 1,000 square-feet each year (this is equal to one normal fertilizer application) to the soil. Second, it saves time since you don’t have to stop frequently to empty the bag. And third, many communities have laws that prohibit the disposal of yard waste in public landfills.

If you follow the 1/3 rule for mowing, the clippings will be small enough that they will decompose rapidly. Grass clippings are more than 90% water and do not contribute to thatch production. If the turf becomes too tall or thick and clippings do need to be collected they can be composted. The high nitrogen content (2–5%) of grass clippings

stimulates microorganisms in compost piles and accelerates the compost process. Clippings can also be used as mulch. However, do not use clippings as mulch in ornamental beds or gardens if you’ve applied herbicides to the grass within the preceding 3 months.

Usually any mower can be used as a “mulching” mower. The simplest mulching mowers don’t have an exit chute, while sophisticated units may have two sets of blades to help cut clippings into smaller pieces.

Fertilizing

Fertilizer labels list three numbers that represent the amount of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium in the fertilizer. General lawn fertilizers in Wisconsin contain nitrogen, and a small amount of potassium. Phosphorus is not allowed to be applied unless a soil test shows the need for phosphorus or if the area is newly seeded or sodded.

Most soils in Wisconsin contain sufficient phosphorus and potassium for established turf, though phosphorus is often useful for promoting germination and establishment of seedlings. An inexpensive soil test will determine the amounts of phosphorus and potassium needed. Nutrients such as sulfur, calcium, magnesium, and others are also used by turf but are plentiful in most soils in Wisconsin so they are rarely added to fertilizer.

Rate

Most lawns require an average of 3 pounds of nitrogen per 1,000 ft2 annually. This is equivalent to three applications using the “normal” rates listed on most fertilizer bags, approximately 1 pound of nitrogen per 1,000 ft2. Use a fertilizer source containing at least 25–50% slow-release nitrogen, often listed as water-insoluble nitrogen on the packaging. Do not exceed 1 pound of nitrogen per 1,000 ft2 at any single application

as the turf will not be able to use all of the nitrogen. Excess nitrogen can cause excessive grass growth, reduce the root growth, encourage some diseases, or even kill the lawn if too much is applied.

Timing

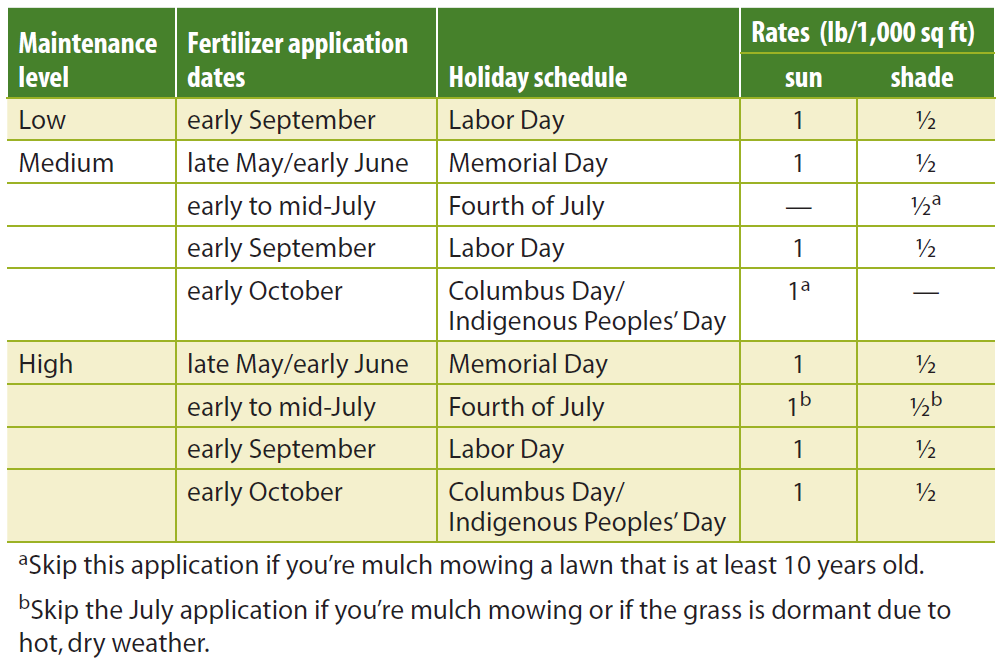

Avoid early spring fertilizer applications (April) as they stimulate leaf growth at the expense of root growth. For high-quality turf, an easy way to remember when to fertilize is to use the “holiday schedule,” fertilizing around Memorial Day, the Fourth of July, Labor Day, and Columbus Day/Indigenous Peoples Day (early October). Low- and medium-quality turf are fertilized less frequently. Table 1 lists the recommended application dates and rates.

If a low- or medium-maintenance (and quality) lawn is desired, few fertilizations are needed. The most important time to fertilize is early September. At this time the grass is actively growing and can fully utilize the applied nutrients. Refer to Lawn Fertilization for additional information.

Lawn fertilizing equipment and technique

There are two types of spreaders, the drop spreader and the broadcast, or rotary, spreader. Each has advantages and drawbacks.

Drop spreaders. As the name indicates, fertilizer falls through holes in the bin of a drop spreader. Drop spreaders allow excellent control of fertilizer placement and are a good choice for small yards and near landscaped beds and open water. The drawback to this precision placement is that any skipped areas will appear lighter green than fertilized areas. To prevent “striping,” make two applications at right angles to each other, using the half-rate setting on the spreader for both passes.

Broadcast spreaders. Broadcast, or rotary, spreaders typically throw fertilizer distances of 10 feet or more. This type of spreader is good for large lawns because you can cover large areas quickly. Rotary spreaders do not apply fertilizer evenly, though, and the majority of the fertilizer is placed within 70% of the actual spread width. To apply fertilizer evenly with a broadcast spreader, either use half the rate and apply in two directions at right angles to one another, or overlap the applications by 30%. Broadcast spreaders should not be used near open water in ditches, ponds, or streams to prevent fertilizer from being applied directly into the water. Also, exercise caution around flower gardens and ornamental plants with this type of spreader.

Irrigating (Watering)

Do I need to water my lawn?

Irrigate the turf during the summer if a high-quality lawn is desired. Low and medium-quality turf may be allowed to go dormant. The leaves will stop growing and turn brown during extended periods of drought but dormant plants can remain alive for 2–3 months. New leaves will grow once sufficient water is supplied for an extended period of time (10 days and longer).

Long stretches of extremely hot, dry weather may kill some of the turf. If large areas do not recover, you may need to overseed or renovate. Review Lawn Establishment and Renovation for more information.

How often should I water my lawn?

Rainfall alone is often sufficient to sustain lawns in Wisconsin. Occasionally, irrigation is needed to maintain a high-quality lawn during dry periods. To keep lawns green throughout the growing season, they should receive approximately 1 inch of water each week, either from rainfall, irrigation, or a combination of both.

Avoid watering more frequently than once a week as that will encourage shallow rooting of the grass plants, making them more susceptible to stress and disease.

How do I measure an inch of water?

To measure the amount of water your sprinkler or irrigation system provides, set a series of several coffee cans, quart-sized jars or similar sized straight-sided containers at 5- to 10-foot intervals from the base of the sprinkler to the end of the irrigation pattern or width. Use the average amount of water collected in each container during a specific time period (e.g., 30 minutes) to determine the amount of water provided by the sprinkler.

When’s the best time to water?

Irrigate the lawn in early morning. This minimizes water loss from evaporation yet allows the sun to dry the leaf surfaces before many diseases can become active. If possible avoid irrigating in the late afternoon or early evening as leaves remain wet longer, which may stimulate disease.

What to do if water runs off

If water begins to run off from your lawn before the sprinkler has applied a full inch of water, split the watering into two or more shorter sessions. Wait a day or two for the soil to fully absorb the water before applying the remainder. Watering to the point of runoff wastes water and may remove nutrients and pesticides from the turf.

Timing Lawn Maintenance

Spring

- Rake the dead leaves and debris from the lawn to help it green up faster.

- Reseed any bare areas.

- Begin mowing for the season, 2½–3½ inches tall, and use the 1⁄3 rule.

- Apply crabgrass preventer if needed.

- Apply fertilizer in late May (use Memorial Day as a guide) for medium- and high-quality lawns.

Summer

- Irrigate high-quality lawns to keep them green and growing.

- Medium- and low-quality lawns can be allowed to go dormant.

- Apply fertilizer around July 4 unless the weather is hot and dry and the lawn is not irrigated.

Fall

- Core aerate if the soil is severely compacted or thatchy.

- Overseed bare areas if needed, especially if it can be done along with core aeration.

- Fertilize around Labor Day for medium- or high-quality lawns.

Lawns and the Environment

Recent research has demonstrated that properly fertilized lawns have considerably less water runoff and nutrient loss than many fields planted with agronomic crops.

However, precautionary measures need to be taken to make sure that the nutrient loss from home lawns remains low. There are some simple steps you can take to help minimize the amount of nutrient runoff from your lawn.

Fertilize your lawn every year. Research has shown that even a single season without fertilization can reduce grass stand density, increasing water runoff by as much as 70%.

- Select fertilizers with at least 25–50% of the nitrogen in slow-release form. This provides a consistent nitrogen source for the turf between applications.

- Sweep up spilled fertilizer. No matter how much care is taken when fertilizing lawns, some inevitably lands on sidewalks, driveways, or in the street. Failure to sweep it up may cause much of it to eventually enter lakes and streams via storm water.

- Water lawns after applying fertilizer. This practice increases the effectiveness of the fertilizer and greatly reduces the potential for nutrient losses during the time of year when short-duration, intense rain storms are a common occurrence.to prune in the morning when plants are turgid (i.e., they have a lot of water in them) so that they snap more easily.

Low-Maintenance Lawns

Low-maintenance lawns require little if any mowing, fertilization, irrigation, or pest control. Such lawns give many people the enjoyment they desire from a turf without the time required for upkeep. Realize, though, that low-maintenance lawns do not fit everyone’s idea of a lawn. They may be prone to weeds, attract rodents such as field mice and ground squirrels, and the higher height of the turf may prevent the area from being useful for recreation.

Plant a seed mixture of at least 50–70% fine fescue species for best results. The mixture should contain one or more varieties of red fescue, Chewings fescue, hard fescue, and sheeps fescue. The rest of the mixture should contain no more than 50% of common or low-maintenance types of Kentucky bluegrass and no more than 15% perennial ryegrass. Fine fescues are slow-growing grasses adapted to low fertility and dry soils.

Mow the lawn once every 2–4 weeks to approximately a 3- to 4-inch height. Fertilize the lawn once or twice annually to delay weed invasion. The lawn may be left unfertilized but will be more susceptible to weed invasion. Mixtures containing only fine fescues are sometimes sold as “no-mow” or “low-mow” mixes. These grasses can be left un-mowed and will grow about 2 feet tall. The orange to reddish seedheads, present from early to late summer, can often add aesthetic appeal to the lawn. Weed the area as needed to remove noxious weeds or woody plants.

Common Lawn Problems

Compacted soils and thatch

Soils become compacted through use. When this happens, plants have difficulty growing because the roots can’t grow deep to access water and nutrients. Compacted soils cause thin (low density) turf and can lead to increased weed problems. The remedy is to remove plugs of soil to loosen compacted soils. This procedure, known as core aeration, improves turf rooting and growth by opening spaces in the soil. It also solves thatch problems by creating a good environment for microbes that degrade thatch.

Core aerators are available for rental at many hardware stores and equipment suppliers. Use self-propelled units with vertically operating tines when possible; tines mounted on drum rollers are less effective because they pull shallower cores. Aerate in the autumn or spring when turf is actively growing. Two to four passes with the core aerator are sufficient. Lawn Aeration and Topdressing describes equipment options and technique in greater detail.

Shaded lawns

Successfully growing turfgrass in the shade can be difficult. Turfgrass plants are naturally adapted to grow in full sun to partial shade. Heavily shaded grass often thins or dies, allowing invasion by moss, algae, and shade-loving weeds such as wood violet (Viola spp.) and Creeping Charlie (Glechoma hederacea). Shady areas require special management practices to keep turf healthy. The following information outlines the key differences. For more details, refer to Growing Grass in Shade.

Plant grass mixtures adapted to shade. For best results, plant mixtures containing at least 50% fine fescues for dry, shaded conditions. For moist, shaded conditions plant mixtures with at least 10% supina bluegrass (P. supina). Do not rely solely on Kentucky bluegrass cultivars listed as shade tolerant. Even the most shade-tolerant of these cultivars prefer more sun than fine fescues, or supina bluegrass.

Use less fertilizer. Apply fertilizer at the same time as for turf in sunny areas but cut the rate in half. Using the full rate on shaded turf temporarily increases leaf growth and prevents vigorous root growth; eventually the turf dies as the root system can no longer deliver enough water and nutrients to the leaves.

Rake or mulch fallen leaves promptly. To maximize the amount of sunlight reaching turf, promptly remove or mulch fallen tree leaves in the autumn. Research shows the leaves can be mulched into the lawn without harming the grass, as long as the blades of grass remain 1–2 inches above the mulched tree leaves.

Consider alternatives to grass for difficult areas. For some areas, shade-tolerant groundcovers or mulches may be a better choice than turfgrass. Refer to Growing Grass in Shade for a listing of plants adapted to low-light areas.

Weeds

Weeds are typically the top problem in lawns. They invade wherever turf is weak or thin. Good cultural management practices (mowing, fertilization, and irrigation) will encourage growth of dense, healthy turf and crowd out and prevent weeds. In fact, with proper mowing and timely fertilization alone you can avoid between 70 and 90% of all weed problems. Herbicides should be used only as a last resort to curb a weed problem. A little herbicide, properly applied, can go a long way. When combined with good management practices, a herbicide application may only be needed every several years.

Select an herbicide based on its ability to control the target weed(s). Factors to consider include the type of weed and the life cycle of the weed (annual, biennial, or perennial). Make sure you have the proper application equipment. Some herbicides are sold in pre-mixed bottles which can be sprayed directly onto weeds. Other herbicides are packaged to be applied using a garden hose. Herbicide concentrates are usually meant to be applied with a hand-held, backpack, or tractor-mounted sprayer, though some may include directions for applying with a hose-end sprayer. Do not purchase more herbicide than you will use within 1 year.

Use herbicides safely to prevent injury to yourself and the environment. Follow the instructions on the herbicide label for proper clothing, handling, and application procedures. If you plan to overseed, follow the directions on the label to make sure the herbicide application does not prevent germination of the seed.

Types of herbicides. Many herbicides are specific for only certain types of weeds; these are termed selective herbicides. Nonselective herbicides (e.g., Roundup, Kleenup) will kill any plant that absorbs the herbicide. Exercise caution when using nonselective herbicides as these will kill both weeds and turfgrass.

Types of weeds. Weeds are classified as grasses, sedges, or broadleaves. Most herbicides control only weedy grasses or broadleaf weeds, not both. Read the label on the herbicide container to determine if the product will control the type(s) of weeds in your turf. Common grassy weeds in turf include crabgrass, foxtail, and quackgrass. Common broadleaf weeds include creeping Charlie (sometimes referred to as ground ivy), dandelion, and clover.

Timing. Pre-emergent herbicides are used to control weeds before they are visible, usually in early spring. Preemergent herbicides are used mostly for control of annual weeds (weeds that live only 1 year) such as crabgrass. Use post-emergent herbicides when weeds are visible.

Postemergent herbicides can control annual, biennial (2-year life cycle), or perennial weeds (live indefinitely). Perennial weeds are best controlled in the fall or in spring when the target weeds are in bloom.

Weed and feed products. Weed and feed products contain both an herbicide and a fertilizer. The herbicide may be for either pre-emergent or post-emergent weed control. Because these products contain an herbicide they should be stored and handled with the same level of care as any pesticide.

Weed and feed products are attractive because it seems as if both weed control and fertility requirements can be achieved with one application. In reality, the pre-emergent weed and feed products generally cause fertilizer to be applied too early in the year for optimal turf response. The post-emergent products often fail to sufficiently control weeds because the weeds absorb too little of the herbicide.

For best results, do not rely on weed and feed products. Instead, fertilize with fertilizer alone according to the schedules listed in table 1. When necessary, use stand-alone preemergent herbicides to prevent infestations of annual weeds such as crabgrass. Existing weeds are best controlled with a liquid herbicide, because a higher concentration of active ingredient can be absorbed by the weeds.

If using weed and feed, apply product equivalent of no more than 1 pound of nitrogen per 1,000 ft2; this application will substitute for one of the fertility applications in the recommended schedule described in the bulletin.

Diseases

The practices described in this publication— proper mowing, fertilization, and irrigation—are the best tools to use to minimize damage from diseases. Some diseases are more common when the turf is overfertilized, others are more common when the turf is under-fertilized. Improper mowing (dull mower blades, removing too much of the leaf)

and insufficient water will stress the turf and make it more susceptible to disease. Watering in the early evening encourages many leaf diseases by keeping leaves moist for long periods. Other fungi may survive in the soil and cause root rots which go unnoticed until periods of drought or other stresses.

Occasionally diseases occur even when good management practices are followed. Well-managed turf has a better chance of recovery than turf that may have been struggling to stay alive before the infection. Proper identification is essential to determine if the disease requires a fungicide treatment or if the turf will recover without fungicide. While there are many diseases of turf, only the most common are described here. For a more complete description of turfgrass diseases in Wisconsin and surrounding states please see Turfgrass Diseases of the Great Lakes Region.

Necrotic ring spot. Necrotic ring spot is caused by a fungus which rots the roots and crowns of turfgrasses. Initially, 3- to 4-inch diameter necrotic, or brown, patches appear in the turf. The areas enlarge to 5–12 inches in diameter as the disease develops. Turf or weeds may fill in the center of older patches, producing a phenomenon referred to as a “frogeye” pattern.

The fungus grows on the roots during cool, wet weather in spring and autumn. Dead patches become noticeable during hot, dry weather because the grass is unable to absorb enough water to stay green. Necrotic ring spot damage is often most severe in the first 2 to 4 years after Kentucky bluegrass sod is installed, but damage tends to decrease over time as the microbial population on the turfgrass roots begins to stabilize.

Cultural practices such as limiting traffic and aerifying to reduce thatch thickness and soil compaction can lessen necrotic ring spot damage. In addition, light and frequent irrigation during hot, dry periods may help the affected turf survive. Adequate fertilization is important to encourage turfgrass recovery once the active infection of the fungus has ended.

Fungicides are not normally recommended for necrotic ring spot control because they have limited efficacy and are difficult to locate down to the roots where the infection occurs.

Kentucky bluegrass and certain types of fine fescue (i.e., hard fescue) can be highly susceptible to necrotic ring spot, while other species such as perennial ryegrass and tall fescue are less susceptible.

Rusts. Rusts occur on all turfgrass species but are primarily observed on perennial ryegrass and Kentucky bluegrass. The primary rust observed on Kentucky bluegrass is stem rust and the primary rust observed on perennial ryegrass is crown rust. The fungus grows inside the plant, often turning the leaves orange or yellow or causing orange or yellow spots. Spores from the fungus eventually erupt through the leaf surface, giving an orange or yellow cast to the turf. This disease occurs during periods of slow turf growth in the late summer and fall.

Rust rarely kills the turf, but it can significantly stunt turfgrass growth, give the lawn an unsightly appearance, and stain shoes and clothes when its spores rub off. To hasten recovery, apply a small amount of fertilizer (up to ¼ pound of nitrogen per 1000 sq ft) and lightly irrigate. Certain families of Kentucky bluegrass, such as ‘Midnight’ types, are highly susceptible to rust and should be avoided in lawn and other low to moderate maintenance situations.

Leaf spot. Leaf spot is caused by two primary types of leaf spot diseases, Bipolaris leaf spot and Drechslera leaf spot. All turfgrass species are susceptible, although heavily fertilized, overwatered turf is most susceptible.

Two phases of the disease, each caused by a different fungus, occur during the year. Drechslera leaf spot occurs during cool, wet weather in the spring and fall. Circular lesions that are purple, yellow, or red in color with distinct brown-colored borders can blight the leaf tissue and discolor the stand of turfgrass. Bipolaris leaf spot occurs during hot and wet conditions during the summer, and red or pink-colored lesions can blight and discolor the turfgrass stand. With both leaf spot diseases, severe infection can lead to plant thinning or death. In most cases, however, the turf is temporarily discolored during infection but the turfgrass recovers once the environmental conditions change and no longer favor fungal growth. Fungicides are generally not recommended for leaf spot control because leaf spot rarely results in turfgrass death.

Powdery mildew. Powdery mildew is caused by a fungus which forms a white powder-like growth on the surface of the leaf. This disease is more prevalent in shady, damp areas and is seen mostly on Kentucky bluegrass. Powdery mildew does not significantly injure turfgrass, but can be associated with thinning turfgrass because of heavy shade limiting photosynthesis of the turfgrass plant. If powdery mildew persists on turfgrass year after year, more shade tolerant turfgrass species like fine fescues or tall fescue can be planted in place of Kentucky bluegrass. In addition, selective pruning or tree removal can increase sunlight penetration and air movement and reduce powdery mildew. Fungicides are not recommended for control of powdery mildew because the disease rarely injures the turf.

Fairy ring. Fairy rings are dark green rings or arcs in turf, ranging in size from several inches to over 10 feet in diameter. Caused by a group of fungi known as basidiomycetes, fairy rings may appear and disappear throughout the year and over the course of a few to many years. All turfgrasses are susceptible. Occasionally, mushrooms grow along the edge of the ring, but the main portion of the fungus is usually deep in the soil. Most mushrooms associated with fairy ring are not toxic to people or pets, but consult with a local mycologist before consuming. Fairy rings develop as fungi decompose organic matter, such as buried stumps, branches, or construction debris. Fairy ring fungi do not actually infect and injure the turfgrass plant, so we typically recommend managing fairy ring by applying a light application of nitrogen fertilizer (up to 0.25 pounds of nitrogen per 1000 sq ft) to mask the dark green ring, or reduce the thatch layer where many basidiomycete fungi live through aerification. Replacing the soil is not an effective fairy ring management strategy since it’s likely the new soil will also have basidiomycete fungi included. Fungicides are not typically recommended for fairy ring control because they aren’t usually very effective and they need to be located down to the soil where the fungi reside.

Snow mold. Snow mold is a general term that encompasses multiple diseases, but the two primary snow mold diseases in Wisconsin are gray snow mold and pink snow mold. Gray snow mold requires about 60 days of continuous snow cover to cause disease, while pink snow mold requires prolonged periods of cool, wet weather (but not actually snow) to cause disease. Gray snow mold damage typically appears as circular patches of tan or brown turfgrass 1 to 3 feet in diameter.

Nitrogen fertilizer applied in late fall can enhance snow mold development and should be avoided. Lawns should be mowed at a height of 2.5 to 3.5 inches right up until winter dormancy to prevent excessively long grass from ‘laying over’ and increasing snow mold. Snow mold damage rarely kills turfgrass, and affected areas should be raked in the spring to promote recovery. Severely affected patches may need to be reseeded. All turfgrass species are susceptible to snow mold, though some species of fine fescue (i.e., hard fescues) show increased resistance to snow molds. Although all turfgrasses are susceptible, tall fescue and perennial ryegrass is generally more susceptible to snow mold than other grass species such as fine fescues and Kentucky bluegrass.

Insect pests

Insect pest problems are rare in Wisconsin lawns compared to many neighboring states because the long winters reduce overwintering insect populations. The most common problems are white grubs and chinch bugs.

White grubs. Grubs are the immature stage of various types of beetles, including Japanese beetles. The grubs feed on turfgrass roots. Their presence often goes unnoticed until drought stress causes plants to die from lack of roots or until animals, primarily skunks, dig up the turf to get at the grubs. Damaged turf looks droughty even though there may be adequate moisture.

Chinch bugs. Chinch bugs feed on the base of turfgrass shoots, causing tan patches of dead turf. Adult chinch bugs are about 1⁄6-inch long and are black with a characteristic white hourglass design on their backs. Immature bugs (nymphs) are smaller than adults and have a broad white line across the back. Several insecticides are available which will control these and other pests. Since different insecticides may be required for specific insects, make sure the pest is properly identified, then select an insecticide which is labeled for control of the pest. Always be sure to read and follow the directions on the label for proper use.

Dog Urine Damage

Dog urine can be damaging to turfgrass lawns (and many other plants) because of its high salt content, which absorbs water from inside the turfgrass leaf plant and results in a brown, tan, or yellow-colored leaf blade. Plants damaged by dog urine are often completely dead, and depending on the size of the damage may need to be reseeded with a seed blend that matches the rest of the lawn. The urine will not prevent germination and growth of new turfgrass seeds, so reseeding can be done at any time after the damage is observed.

Unfortunately there are no products that prevent damage from dog urine. Care can be taken to drench the affected area with water immediately after the dog urinates, but this is usually not practical. More often it’s recommended to train the dog to urinate in a mulched area where the urine won’t harm plants.

Diagnosing Lawn Problems

There can be many reasons for poor turf performance and it is not uncommon for a variety of problems to interact. You may need to seek outside expertise for help identifying the problems. One of the best steps is to submit photos and details of your problem to our Ask Your Gardening Question form.

Samples may also be sent to the Turfgrass Diagnostic Lab of the University of Wisconsin. To submit a sample, cut a circular or square area of the turf, at least 4 x 4 inches, which includes both affected and a healthy turf. Keep about an inch of soil at the bottom of the sample. Wrap the sample loosely in newspaper, followed by aluminum foil. Do not place the sample inside a plastic bag, which can cause the sample to deteriorate in transit.

Completely fill out the ‘Homeowner Submission Form’ provided on the Turfgrass Diagnostic Lab website and include it along with the sample. Place the wrapped sample and the submission form in a box and ship to the Turfgrass Diagnostic Lab. If mailing your sample, send it early enough in the week so it arrives no later than Thursday.

Pesticide labels change often

Always read the pesticide label prior to use. Persons using pesticides are responsible for their use according to current label directions of the manufacturer.