Yellow toadflax (Linaria vulgaris), also called butter and eggs or wild snapdragon, is one of about 130 species of Linaria native to Eurasia. Many weedy species of Linaria resemble true flax (Linum usitatissimum) in leaf shape and arrangement. Yellow toadflax is an escaped ornamental brought to this country in the mid-1800’s. It was used as a yellow dye for centuries in Germany, so immigrants, especially the Mennonites, cultivated it for use in dyeing.

This perennial plant in the figwort family (Scrophulariaceae) occurs throughout most of temperate North America and is listed as a noxious weed in several western U.S. states and Canadian provinces. Because it contains a poisonous glucoside that may be mildly toxic to livestock, it is a particular problem in rangeland (although it is also unpalatable, so reports of livestock poisoning are rare). It is typically found in open, disturbed sites such as roadsides and waste areas or in fields, pastures, edges of forests and rangeland, where it can displace desirable grasses.

This species is occasionally used in flower gardens for its showy flowers but it should be used with caution as it can easily escape and spread aggressively. It has also been included in wildflower mixes, so check the species list carefully (and don’t use mixes that don’t identify the contents).

The related Dalmation toadflax (L. dalmatica, from southeastern Europe around the Mediterranean) is another escaped ornamental that is very similar to yellow toadflax. It is a larger, more robust plant with increased branching near the top of the plant and has a different type of leaf. It was introduced in North America around 1900. Yellow toadflax, which is adapted to moister soils, is more common throughout eastern North America while Dalmatian toadflax is more common in the western United States, although both can be found throughout the continent.

The easiest way to distinguish between yellow and Dalmation toadflax is by the leaves. The lance-shaped, gray-green, 2” long leaves of yellow toadflax are stalkless and pointed at both ends. Dalmatian toadflax has clasping, heart-shaped or egg-shaped leaves. The leaves of both species are alternate but may appear to be opposite because they are crowded together.

The plants begin growing from the roots as soon as the soil warms in early spring. Plants can grow up to 3 feet tall, but are generally much shorter (1-2 feet tall). Yellow toadflax spreads both by seed and extensive creeping rhizomes and therefore typically occurs in patches. The roots of a single plant can extend 10 feet and give rise to daughter plants every few inches. This aggressive perennial is able to quickly colonize open habitats and often outcompetes other plants, including natives, but will be displaced by other species when growing in less favorable conditions. Plants growing in dry soils tend to be stunted but are relatively persistent.

In the summer through fall bright yellow or cream snapdragon-like flowers are produced in crowded terminal clusters (the flowers of Dalmatian toadflax occur in the axils of the upper leaves and bracts and bloom earlier in the season). Each of the 1” flowers has an orange spot on the lower lip (orange bearded throat) and a ½” long straight spur. As the flowers mature, the orange patch becomes more distinct. The flowers are attractive to bees, butterflies, and other insects.

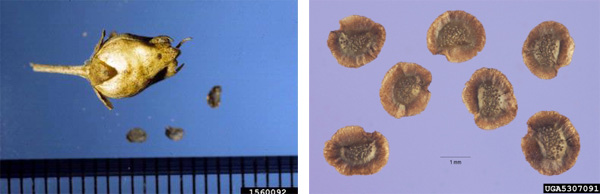

Round, dark colored seeds are produced in brown, globe-shaped capsules. Each seed has a notched, papery collar that aids in dispersal. Although seed viability is generally low, the winged seeds may disperse over a long distance in the wind, or may be moved by water and ants. Seeds may remain dormant in the soil for up to 10 years.

Yellow toadflax is difficult to eradicate, due to its extensive root system. Root fragments as small as 1/2″ long can produce new plants. Tillage beginning in the early summer and continued at 3-4 week intervals has been somewhat successful in controlling this weed. Mowing will help decrease seed production but will generally not eliminate established populations. Burning is not effective, as it doesn’t kill the roots. Many populations are resistant to herbicides but several chemicals are used as spot-treatments. The best time for treatment is at the beginning of flowering.

Control of this weed on rangeland is much more difficult than in cultivated or landscaped areas. Disturbed areas can be seeded with certain vigorous, well adapted grasses which will outcompete yellow toadflax. Several biological control agents (a defoliating moth, a seed head weevil, and a flower beetle) have been released in the west to provide from fair to good control. The weevil Gymnetron antirrhini, which develops inside the fruit as a larva and feeds on the leaves, buds and stems as an adult, is the most important species in many parts of North America. Other species include another weevil (Mecinus janthinus) that bores in the stems as larvae and feeds on shoots as adults; the leaf-feeding moth Calophasia lunula, which has a very limited distribution; and another moth species (Eteobalea serratella) that mines the roots. This last species reduces the competitive ability of yellow toadflax, shortens the flowering season and lowers seed weight, and complements other biocontrol agents.

– Susan Mahr, University of Wisconsin – Madison

Ask Your Gardening Question

If you’re unable to find the information you need, please submit your gardening question here: