Authors: P.J. Liesch, Josie Dillon, Vijai Pandian, and Christelle Guédot (formerly Extension)

Revised: 1/23/2026

Overview of Spotted Lanternfly

Spotted lanternfly (SLF) is an invasive planthopper (Lycorma delicatula | Hemiptera: Fulgoridae) not native to North America. This insect has a broad host range (100+ plant species) and poses threats to the grapes, tree fruits, hops, and landscape plants. SLF was first detected in the U.S. in eastern Pennsylvania in 2014.

Since its introduction to North America, SLF has spread across the eastern U.S. and is present in over 15 states. The bulk of the SLF infestation is currently centered around southern Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, and New Jersey. However, this invasive insect has spread outwards from that core area and is now known to have established in parts of Ohio, Indiana, eastern Michigan, and the Chicago area of Illinois. See this page from Cornell University for the latest on the distribution of SLF in the United States. As of early 2026, live SLF specimens have not yet been detected in Wisconsin. Modeling studies suggest that SLF is unlikely to be an issue for northern Wisconsin based on environmental conditions, but could be problematic in southeastern parts of the state.

Appearance

Spotted lanternfly adults are approximately 1 inch long and ½ inch wide at rest; the extended wings have a span of roughly 1.5 inches. The insects’ forewings are greyish with black spots at the base and have a grey, lace-like pattern towards the tips. The hindwings are bright red with black spots at the base, have white bands near the center, and have a black net-like pattern towards the tips. Most of the time, adults hold their wings over their bodies which obscures the hindwings. The head and legs of SLF adults are black, while the abdomen is yellow with broad black bands. Adult female SLFs have reddish structures at the tip of their abdomens.

Spotted lanternfly egg masses are 1 – 1½ inches long and ½ – ¾ inches wide and contain 30 – 50 eggs. The eggs are greyish-brown, but are covered with a grey, putty-like coating which is initially glossy in appearance. This covering eventually breaks down and the individual eggs can be exposed over time. The youngest SLF juveniles (nymphs) are wingless and black with white spots. As nymphs mature, they eventually develop red patches, but retain some black coloring with white spots. Both adults and nymphs possess tubular, sucking-type mouthparts, which they use to pierce plants to ingest fluids.

Host Plants

Spotted lanternfly has a wide host range (100+ plant species) that changes slightly over the course of their lifecycle. Nymphs appear to feed on leaves and branches of virtually any plant they encounter, often gathering in large numbers. Young nymphs prefer herbaceous plants or tender shoots of trees and shrubs. As they mature, older nymphs move to tougher, woody plants to feed. Adults are found primarily on woody plants. In the fall, SLF adults can congregate in large numbers on host plants. The highest numbers tend to be found on preferred hosts such as tree of heaven and grapes. However, adults can be found on a range of host plants, including, black walnut, willow, maple, birch, poplar, tulip poplar, ash, oak, apple, and stone fruit trees (e.g., cherries and plums).

Tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima) is a preferred host plant for SLF. Tree of heaven is an invasive, non-native plant that grows in disturbed sites and along roadsides and railroads. Since it is a preferred host, tree of heaven may serve as a key indicator plant for SLF. Learn to identify tree of heaven through this resource from the Wisconsin First Detector Network.

Damage

Spotted lanternfly feeds on plants as both nymphs and adults. Some good news, however, is that SLF generally does not kill plants. However, it can contribute to plant stress, especially during periods of unfavorable growing conditions (e.g., drought).

SLF adults and nymphs feed on a plant’s phloem (i.e., food conducting tissues), sucking the sap from young stems and leaves, which weakens plants. Discoloration and wilting of affected leaves can potentially occur. Affected plants often have weeping/oozing wounds on their trunks that eventually result in greyish-black discolorations. In addition, SLF excretes large amounts of sticky honeydew (i.e., sugar-rich droppings) which can cover stems and leaves and build up on the ground at the base of plants. Honeydew can also be an unsightly mess if it drips onto patio furniture, decks, automobiles, driveways, parking lots, or other items/areas. Honeydew can promote the growth of sooty mold fungi, giving leaves and branches an unsightly blackish coating that can further reduce photosynthesis and contribute to plant stress. Oozing sap and honeydew can promote the growth of other microbes and also attract secondary insects such as wasps, bees, and ants.

From an agricultural perspective, damage to grapes is the primary concern as crop health and yields can potentially suffer. In locations where SLF is established, growers may need to apply additional insecticide applications to manage this pest. Tree fruits (e.g., apples, plum, etc.) and hops can also be affected, but to a lesser extent, and SLF is expected to be a minor/nuisance issue in such crops. SLF can affect young trees grown in plant nurseries.

Damage from SLF can weaken overall plant health. While most established landscape plants are unlikely to be killed by SLF, feeding by this insect can stress plants and make them more sensitive to secondary issues (e.g., attack by other insects, diseases, unfavorable weather conditions). Some good news is that recent research from the eastern U.S. suggests that spotted lanternflies are more of a nuisance than a threat to the health of established residential yard trees.

SLF is generally harmless to humans and pets and is not capable of biting or stinging.

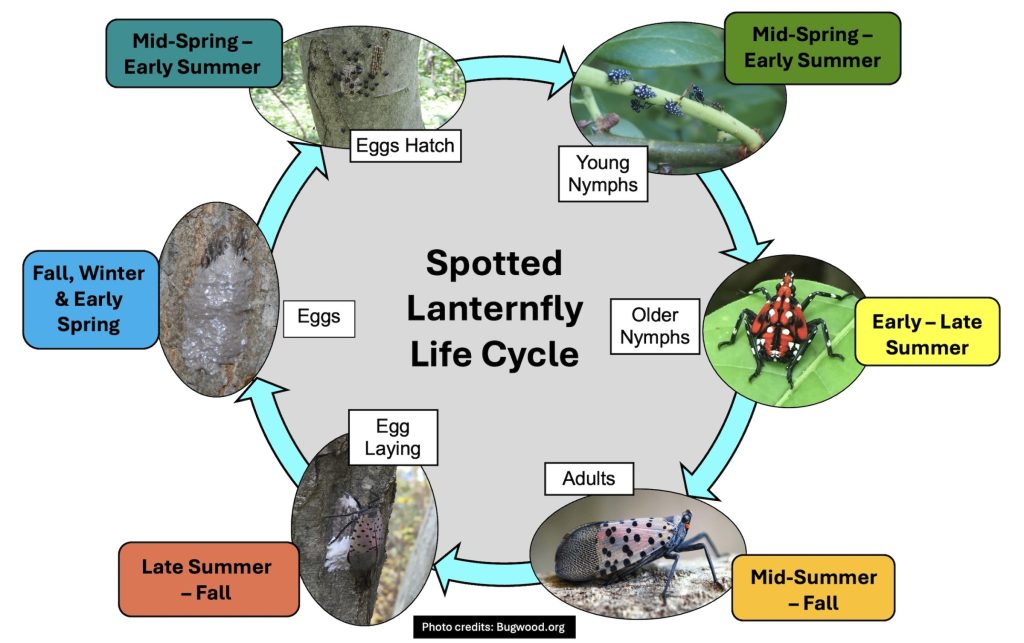

Life Cycle

Spotted lanternfly has only one generation per year and overwinters as eggs in egg masses. In the spring and early summer, eggs hatch and SLF nymphs (juveniles) go through four stages called “instars”. The appearance of the nymphs and their plant feeding preferences shift as they mature. Adults begin to appear in mid-summer. Males and females mate multiple times, resulting in females producing one or two egg masses in late summer to fall until they succumb to cold temperatures. Spotted lanternfly females lay egg masses on smooth surfaces, such as smooth-barked trunks, branches, and limb bases of medium to large-sized trees; on smooth stone and other natural surfaces, and on man-made items such as yard furniture, cars, trucks, and farm equipment.

Movement of Spotted Lanternfly

Spotted lanternflies primarily walk and jump to move, so they don’t travel far on their own. Nymphs lack wings and while adults do have wings, they are weak fliers. The main reason for rapid dispersal across the U.S. has been the human-assisted movement of this insect in its various life stages. In particular, the egg masses can easily be transported if present on vehicles, pallets or other shipping materials, nursery stock and other natural or man-made items.

Scouting Suggestions for Spotted Lanternfly

Spotted lanternfly nymphs and adults gather in large numbers on host plants and are easy to find as they migrate up and down tree trunks. SLF can be especially active at dusk or after dark, but can also be found during the daytime hours. Beginning in spring and into summer, watch for nymphs on smaller plants and vines, and on any new growth on trees and shrubs. Watch for SLF adults in late summer into the fall, when they can be found in large numbers. Sticky tree band traps can be helpful for monitoring for young SLF nymphs, but less useful in detecting older nymphs and adults. See the General Management section below for details about how to properly use sticky band traps. From fall to spring, watch for SLF egg masses, particularly on tree of heaven.

General Management of SLF

SLF has not yet been found in Wisconsin and early detection is critical. Before attempting to control spotted lanternfly, report any suspected detections to the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection (DATCP) at this page (See “Report a Spotted Lanternfly Sighting” in the menu).

Spotted lanternfly will primarily be a nuisance issue rather that a threat to landscape plants, so tolerating their presence will be an option in many situations. In other cases (e.g., grape growers), management may be required. A range of management options for SLF are summarized below.

Many factors, including the type, size, and number of affected plants, size of local SLF populations, time/resources available for management activities, and personal preferences (e.g., non-chemical, organic, etc.), will influence management decisions.

Cultural Control:

- Tolerance. In most residential settings, SLF will be a nuisance, but will not kill established trees or shrubs. If aesthetic impacts are not of concern in a given area, taking no action is a feasible option.

- Promote plant health. Good horticultural practices that enhance plant health may make trees and other plants more resilient and better able to withstand feeding damage from SLF. This may be especially true during periods of adverse environmental conditions (e.g., proper watering during periods of drought).

- Remove preferred host plants. Removal of certain infested host trees, such as the invasive tree of heaven can reduce the impacts of SLF. See this publication on controlling tree of heaven from UW-Madison Division of Extension.

- Inspect before you go. This can be done anytime of the year. Because human-assisted transport is known to be a key method of spread, inspecting vehicles and materials before transporting them is an important step to minimize the chances of moving SLF eggs or other life stages to a new area. An example checklist for the general public can be accessed from the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture. Nursery managers and other plant industry professionals can find additional guidance from the Wisconsin Department of Agriculture Trade and Consumer Protection.

Biological Control:

- Encouraging Natural Control Methods. In its native range, other organisms (i.e., predators, parasites, and pathogens) are believed to naturally help keep SLF populations in check. While some of our local predators, parasites, and pathogens may attack and feed on SLF, research suggests that their impacts are limited at this point in time. Nonetheless, planting a diverse range of flowering plants native to Wisconsin can help attract beneficial predators and parasites and may provide some benefit in regard to the management of SLF and other pests. Additional research on the biological control of SLF is ongoing.

Physical Control:

- Physically scrape off and destroy SLF egg masses. This can be done from fall through winter and into spring. Use a putty knife or similar tool to physically scrape egg masses from trees, shrubs, and man-made objects. Use caution to avoid damaging plants while doing this. Egg masses should be collected in a container of soapy water to kill them. If egg masses are simply allowed to fall on the ground, nymphs may still emerge in spring. Unfortunately, research has found that the majority of egg masses are generally inaccessible (>10 ft above ground), limiting the effectiveness of this approach. Nonetheless, this can be an important approach when inspecting vehicles and man-made items before transporting them.

- Physically crush or remove SLF nymphs and adults. This could be accomplished by crushing with a tool or physically removing them with the hose attachment of a vacuum cleaner. This is an option during the growing season, but is limited to SLF individuals that are safely within reach. In addition, this approach can be time consuming and would need to be done throughout the growing season to maximize effectiveness. It is not feasible for large areas.

- Traps. Traps can be particularly helpful for nymphs in spring and into summer. Traps can be placed onto tree trunks to intercept and capture nymphs as they climb upwards to feed in the canopy of trees. Penn State University has instructions on how to build a trap here. In addition, sticky barrier traps, similar to those used for spongy moth caterpillars, can be considered. If used, suspend mesh chicken wire or similar material over the sticky traps to prevent other wildlife from contacting the sticky surface.

Chemical Control:

- Dormant oil treatments. Treat egg masses with a dormant spray oil prior to hatch. Golden Pest Spray Oil (OMRI-Listed) is a product labelled for treatment of egg masses of spotted lanternfly and spongy moth. This product smothers and suffocates eggs when sprayed directly onto egg masses. This can be done from fall through winter and into spring, but temperatures need to be 40˚F or above with no risk of frost.

- Organic & Low-Toxicity Contact Sprays. During the growing season, a number of sprays are available that are labelled for organic use or have lower non-target impacts than their alternatives. These include insecticidal soaps, horticultural oils (including neem oil), pyrethrins/pyrethrum, and azadirachtin. Many of these products work by contact and must be applied directly to the insects to work. With some of these products (e.g., oils), the potential for phytotoxicity exists. Be sure to read and follow all instructions on the pesticide label and consider spot treating a small part of a plant to check for phytotoxicity. Since these products are applied with a pump sprayer, they’re most appropriate for small plants that can be reached (e.g., shrubs and trees <15 feet tall).

- Conventional contact sprays. A number of conventional insecticide sprays are available at hardware stores and garden centers. These are typically broad-spectrum products and can pose greater risk to other insects, such as beneficial predators and pollinators. Common ingredients from this group include pyrethroid ingredients (e.g., bifenthrin, cyfluthrin, cypermethrin, permethrin, etc.) and carbaryl. Such products do provide residual activity and typically last 1-2 weeks. Since these products are applied with a pump sprayer, they’re most appropriate for small plants that can be reached (e.g., shrubs and trees <15 feet tall).

- Systemic treatments. For larger trees, a few systemic ingredients are available to homeowners. The common systemic treatments available include imidacloprid and dinotefuran. These are typically applied as a soil drench at the base of trees or as a spray to the lower part of the trunk (dinotefuran). Arborists have additional options as well, such as trunk-injection treatments. Visit the Wisconsin Arborist Association website to find an arborist in your area. Both imidacloprid and dinotefuran are neonicotinoid insecticides and are known to be highly toxic to bees and other pollinators. Therefore, they should be applied to plants after bloom has occurred for the year. Also, consider if systemic treatments are needed, as SLF is unlikely to kill established landscape trees and shrubs. Due to the mobility of the small nymphs, their host preferences, and the timing of their activity, systemic treatments are generally used to target older nymphs and adults on larger woody plants (i.e., trees).

Management Considerations for Fruit Growers

This section contains information relevant to fruit growers. See the General Management section above for additional details as well.

Wide-spread economic damage to fruit crops has been relatively rare in states with active spotted lanternfly populations. However, significant damage to grape vines has occurred and damage to grapes is the primary agricultural concern as both crop health and yields can potentially suffer. In locations where SLF is established, grape growers may need to apply additional insecticide applications to manage this pest. Tree fruits (e.g., apples, plum, etc.) and hops can also be affected, but to a lesser extent. SLF is expected to be a minor/nuisance issue in such crops, but could be a concern for “You-Pick” farms as visitors may dislike the presence of SLF and/or the aesthetic issues resulting from honeydew.

Spotted lanternfly damage to fruit crops ranges from direct, early-instar nymph feeding on new, herbaceous growth to 4th-instar nymph and adult feeding on established woody branches and trunks. Spotted lanternfly feeding may result in wilting or yellowing leaves, leaf loss, reduced winter hardiness, and depletion of available carbohydrates. SLF feeding is more impactful on young trees and vines, and could contribute to plant declines and yield losses. As SLF feeds, it excretes a sugary substance called honeydew that may attract other nuisance pests or diseases. For example, sooty mold will often grow on excreted honeydew, coating branches, leaves and trunks.

In vineyards and orchards, adult SLF have been observed swarming on a single or small group of trees or vines, and can be more common along edges of fields. SLF aggregations may be alarming, but are often localized to a single tree/vine or small a small area. Thus, spot treatments may be appropriate for localized SLF issues.

Cultural Control:

- Host Plant Monitoring and Removal. Wisconsin fruit growers can proactively prepare for future SLF populations by scouting for and removing nearby host plants. The most important SLF host plant is the tree of heaven, which is also invasive. In addition, traps (see physical control below) can be used on preferred host plants (i.e., tree of heaven) to monitor for SLF activity.

- Promote plant health. Good horticultural practices (e.g., irrigation, fertilization, pruning, etc.) may make fruit trees and vines more resilient and better able to withstand feeding damage from SLF.

Biological Control:

- Parasites and pathogens. Some local predators, parasites, and pathogens may attack and feed on SLF, but research suggests that their impacts are currently limited. Research is ongoing and scientists are currently evaluating two species of fungi (Clifton et. al., 2021) and several parasitic isnects that targeting eggs and nymphs (Xin et. al., 2021).

Physical Control:

- Physically scrape off and destroy SLF egg masses. In late summer and fall, SLF will lay eggs in large, flat, tan-colored masses on a variety of surfaces. Fruit growers can remove and destroy SLF egg masses laid on branches or trunks while winter pruning. Egg mass removal will not completely eliminate SLF, but may help reduce overall population growth from year to year.

- Netting. Mesh netting can be deployed as a physical exclusion method to prevent SLF feeding on trees/vines (Leach et., al., 2023).

- Traps. Penn State has developed two traps, tree bands and circle traps, that growers can use to monitor SLF populations. It is recommended to place traps on nearby Tree of Heaven. Check out these resources from Penn State on How to Build a Spotted Lanternfly Circle Trap and Spotted Lanternfly Tree Banding. Trapping will not eliminate SLF and is most useful as a monitoring tool to identify local activity and inform future management efforts.

Chemical Control:

- Out of all the fruit crops, SLF poses the greatest concern for grapes and grape growers may need to apply additional insecticide sprays to manage this insect. SLF pose lesser concerns for tree fruits and hops and insecticide sprays will not be needed in many situations.

- Conventional Insecticide Options. Growers dealing with SLF in the eastern U.S. have had success with a range of products protecting fruit crops such as grapes with foliar sprays. Active Ingredients that have worked well in field trials include: beta-cyfluthrin, bifenthrin, carbaryl, dinotefuran, fenpropathrin, malathion, thiamethoxam, and zeta-cypermethrin. Additional details about management of SLF in vineyards is detailed in this resource from Penn State.

- Organic options. A number of organic options exist, including neem oil, horticultural and dormant oils, insecticidal soaps and pyrethrins. Fruit growers can also review this SLF spray guide from Cornell University for further guidance. The list includes commercial and home fruit grower options.

- The mention of a pesticide product or ingredient is not an endorsement. Review pesticide labels before applying and ensure each product is registered for use in Wisconsin.

Extension Resources for SLF Management in Fruit Crops:

Peer Reviewed Resources for SLF Management in Fruit Crops:

- Clifton, E.H. , Castrillo, L.A. and Hajek A.E. (2021). Discovery of two hypocrealean fungi infecting spotted lanternflies, Lycorma delicatula: Metarhizium pemphigi and a novel species, Ophiocordyceps delicatula. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 186: 107689. doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2021.107689

- Leach, H. (2021). Evaluation of Residual Activity of Insecticides for Control of Spotted Lanternfly in Grape. Arthropod Management Tests. 46(1).

doi.org/10.1093/amt/tsaa123 - Leach, H., Biddinger, D.J., Krawczyk, G., Smyers, E. and Urban, J.M. (2019). Evaluation of insecticides for control of the spotted lanternfly, Lycorma delicatula,(Hemiptera: Fulgoridae), a new pest of fruit in the northeastern U.S. Crop Protection. 124:104833. doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2019.05.027

- Leach, H., Mariani, T., Centinari, M., & Urban, J. (2023). Evaluating integrated pest management tactics for spotted lanternfly management in vineyards. Pest Management Science. 79(10), 3486–3492. doi.org/10.1002/ps.7528

- Xin, B., Zhang, Y., Wang, X., Cao, L., Hoelmer, K.A., Broadley, H.J. and Gould, J. (2021). Exploratory Survey of Spotted Lanternfly (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae) and Its Natural Enemies in China, Environmental Entomology. 50(1), 36–45. doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvaa137

Additional Resources

- Spotted Lanternfly Overview (video, WI-DATCP)

- Spotted Lanternfly Industry Training (video, WI-DATCP)

- Tree of heaven: A listed invasive plant in Wisconsin (video, UW-IPCM)

Acknowledgement:

Thanks to Michelle Bogden Muetzel, Michael Falk, Mitchell Lannan, Mark Renz, Bret Shaw, and Matt Wallrath for reviewing the article.

Spotted Wing Drosophila

Spotted Wing Drosophila Black Stem Borer

Black Stem Borer Viburnum Leaf Beetle

Viburnum Leaf Beetle Blueberry Maggot

Blueberry Maggot