Most people recognize the word aloe in conjunction with the therapeutic, cosmetic, and medicinal properties of the leaf sap of Aloe vera. This is a commonly cultivated plant widely available almost anywhere plants are sold. Many people have a small plant growing in the kitchen window, close at hand in case of burns from cooking or other household tasks. Aloe vera has been in human cultivation for over 2000 years and has likely been “improved” by selection of forms with greater therapeutic value throughout that period. Interestingly, what we call Aloe vera today is not definitely known as existing in nature, though similar plants are known from Oman on the Arabian Peninsula. Because of its useful properties, Aloe vera has been cultivated in areas of mild climate throughout the world.

Aloes have been placed in various plant families; initially they were in the Liliaceae. Today taxonomists place them either in the Asphodelaceae (with asphodels and red hot pokers) or Aloaceae (with a few other related succulent genera). The genus Aloe is native to Africa, especially the drier areas of southern and eastern Africa and the neighboring island of Madagascar, and southern Arabia. The genus is large, with well over 400 named species, and new types are still being found in out-of-the-way places. Plants vary in size from massive, heavily branched trees over 60 ft tall to tiny ground-hugging plants barely an inch in diameter.

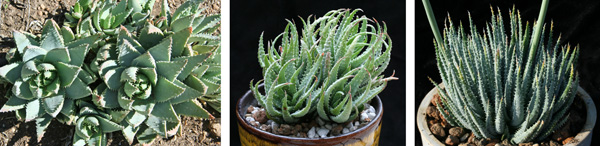

The plants generally have highly succulent leaves, usually in a rosette pattern, though a few hold their leaves in a fan-like pattern, and several small species that live in grasslands have very slender, though still succulent, grass-like leaves.

The tubular to bell-shaped flowers are produced in loose to tight, cylindrical, conical, or head-like clusters (racemes) on branched or unbranched slender stalks and are predominantly various shades of pink to red, though orange and yellow colors are also common and white and green are also known. Bicolor flowers are not uncommon.

Leaves are often attractive, variously colored in hues of green, red, pink, and lavender, and ornamented with stripes, spots, bumps, and teeth.

Aloes are very popular with growers of cacti and succulents and other exotic houseplants. Medium to large species are usually adapted to full sun and require high light intensity to maintain healthy and typical growth. Such large species are best left to those who live in mild climates where they can be grown continuously in the ground; because of their interesting shapes and highly attractive flowers, they are popular landscaping plants in southern California and other relatively frost-free locations.

In nature, smaller Aloe species often grow partially shaded by rocks or other vegetation and these types are well suited for growing under lower light conditions, though at least several hours of bright light daily are still needed for ideal growth, more colorful leaves, and more reliable flowering. No species will survive our winters so here in Wisconsin they must be grown as container plants. These are best kept outdoors with at least some full sun during the summer and moved to a bright location indoors during prolonged cool, cloudy, wet weather and during our frost and freeze period of the year. There are many types of small species and hybrids from which to choose; some can be happy growing slowly for years in a 4” pot, while others will eventually grow to fill an 18” container, with every size in between. Many species produce offsets and eventually will form an attractive clump; others stay solitary. Cuttings root readily.

Aloes have been the subject of hybridizers for years, and some amazing, almost unbelievable hybrids are available through specialty succulent plant nurseries, though newer, more exotic (and rarer) hybrids can have a sizeable price tag (up to $40). There are many dozens (hundreds?) of named hybrids and they come in all sizes, from landscape specimens to tiny miniatures. Previously it required many years to propagate selected hybrids by normal vegetative techniques. Today, desirable hybrids are quickly propagated in tissue culture labs.

Aloes are best grown in a well-drained potting mix, in a pot with a drainage hole. The roots should not be allowed to be continuously wet – allow the soil to dry between waterings. Most aloes are from summer rainfall areas and therefore are summer growers. In Wisconsin, even the smaller types can be given full outdoor sun in the summer, and, if the soil is very well drained, can tolerate frequent rains, especially during the warmer months of summer. When the weather is cool and cloudy they are best kept on the dry side, including during the winter when they are less actively growing. Most aloes are very cold sensitive and should be protected from prolonged temperatures below 50°F; certainly protect from frost. During their winter rest period smaller plants can be grown in a bright windowsill, though keep in mind they should not be allowed to suffer temperatures much below 55°F, so you may want to take them off the windowsill during those -30°F nights.

Small aloe species and hybrids often bloom when only a few years old. Different species will bloom at different times of the year but many bloom in winter (January to March), providing a nice splash of color during a dull time of the year. Aloe plants are more likely to bloom if they get abundant light throughout the year, so be sure to provide them a bright location in winter. Given ideal conditions, some small species and hybrids bloom almost continuously for months on end, sending up new flower stalks when the old ones fade.

Aloes can often be found in the mixed cactus and succulent offerings of the large chain stores. Many of these are generically labeled “Aloe species” or “Aloe hybrid” or are misnamed, so be prepared for the “cute little puppy” to possibly grow into a Labrador Retriever. There are also many reputable mail-order cactus and succulent nurseries on the internet.

The following alphabetical list includes small and dwarf species aloes that are in cultivation, some more readily available than others. (Because of the numerous hybrids now available, none are listed.) The country of origin of each is given. All of those listed generally form clumps, though some, such as longistyla and parvula may be slow to do so. If you have space for somewhat larger pots, to accommodate plants up to 12-15”, this list could be much longer. The following codes are used:

# = diameter of individual plants: sm = small (3-8”); dw = dwarf (under 3”)

? = less commonly available; may be more expensive

! = a bit touchy to grow

- albiflora (Madagascar) #sm

- aristata (South Africa) #sm

- bakeri (Madagascar) #sm

- bellatula (Madagascar) #sm

- bowiea (South Africa) #dw

- brevifolia (South Africa) #sm

- calcairophila (Madagascar) #dw, ?, !

- descoingsii and subsp. augustina (Madagascar) #dw

- droseroides (Madagascar) #dw, ?, !

- florenceae (Madagascar) #dw, ?

- fragilis (Madagascar) #dw, ?

- haworthioides (Madagascar) #dw

- humilis (South Africa) #dw-sm

- inexpectata (Madagascar) #dw, ?, !

- juvenna (Kenya) #dw

- krapohliana ssp. dumoulinii (Namibia) #dw-sm, ?

- longistyla (South Africa) #sm, ?

- parvula (Madagascar) #dw

- pseudoparvula (Madagascar) #dw-sm, ?

- rauhii (Madagascar) #dw-sm

- sladeniana (Namibia) #dw, ?

- variegata (South Africa) #dw

– Dan Mahr, University of Wisconsin – Madison

All photographs © Daniel L. Mahr

Marigolds

Marigolds Create a Butterfly Garden

Create a Butterfly Garden Plant Flowers to Encourage Beneficial Insects

Plant Flowers to Encourage Beneficial Insects Forcing Bulbs

Forcing Bulbs